Iva Toguri D’Aquino, the Japanese-American convicted of treason in 1949 for broadcasting propaganda from Japan to United States servicemen during World War II as the seductive but sinister Tokyo Rose, died Tuesday in Chicago. She was 90.

Iva Toguri D’Aquino, the Japanese-American convicted of treason in 1949 for broadcasting propaganda from Japan to United States servicemen during World War II as the seductive but sinister Tokyo Rose, died Tuesday in Chicago. She was 90.Her death, at a Chicago hospital, was confirmed by a nephew, William Toguri, who said only that Mrs. D’Aquino had died of natural causes, The Associated Press reported.

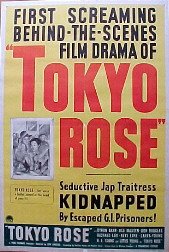

Tokyo Rose was a mythical figure. The persona, its origin murky, had been bestowed by American servicemen collectively on a dozen or so women who broadcast for Radio Tokyo, telling soldiers, sailors and marines in the Pacific that their cause was lost and that their sweethearts back home were betraying them.

The broadcasts did nothing to dim American morale. The servicemen enjoyed the recordings of American popular music, and the United States Navy bestowed a satirical citation on Tokyo Rose at war’s end for her entertainment value.

But the identity of Tokyo Rose became attached to Mrs. D’Aquino, a native of Southern California and the only woman broadcasting for Radio Tokyo known to be an American citizen. She emerged as an infamous figure in a rare treason trial.

Convicted by a federal jury in San Francisco on one of eight vaguely worded counts, she was sentenced to 10 years in prison and a $10,000 fine. She served 6 years and 2 months, then lived quietly in Chicago, running a family gift shop. On Jan. 19, 1977, she was pardoned, without comment, by President Gerald R. Ford on his last full day in office, and her citizenship was restored.

“A mere wartime myth, Tokyo Rose was to become a disgrace to American justice," Edwin O. Reischauer, the American Ambassador to Japan from 1961 to 1966 and a scholar at Harvard specializing in East Asian affairs, wrote in his introduction to “Tokyo Rose: Orphan of the Pacific,” by Masayo Duus. (Kodansha International, 1979)

The treason charges, Mr. Reischauer wrote, were “egged on by a public still much under the influence of traditional racial prejudices and far from free of the anti-Japanese hatreds of the recent war."

Iva Ikuko Toguri was born in Los Angeles on the Fourth of July 1916, a daughter of Japanese immigrants who owned a grocery store. She graduated from U.C.L.A. in 1940 with a d

egree in zoology, hoping to become a physician.

egree in zoology, hoping to become a physician.In the summer of 1941, she visited an ailing aunt in Tokyo at the request of her mother. When the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor, she was stranded in Tokyo, knowing virtually no Japanese, deprived of a food ration card by the authorities after refusing to become a Japanese citizen and hard-pressed to find work.

In 1942, she obtained a job with Japan’s Domei news agency, monitoring American military broadcasts, and late in 1943 she became an announcer and disc jockey for Radio Tokyo’s propaganda broadcasts, playing American musical recordings on the “Zero Hour” program beamed to American servicemen. She called herself “Ann” or “Orphan Ann,” short for announcer and a play on the Orphan Annie character.

While continuing to work for Radio Tokyo in 1945, she married Felipe D’Aquino, a Domei news agency employee with Portuguese citizenship but Japanese ancestry.

When the war ended, several American reporters learned of Mrs. D’Aquino’s broadcasts and interviewed her in Japan. She said that she was Tokyo Rose, evidently presuming that no great notoriety would be attached to that and perhaps hoping to embellish an intriguing story for American readers, having been paid for her account in a magazine article. She subsequently denied ever having called herself Tokyo Rose in her broadcasts, and no evidence was produced to the contrary.

As an outgrowth of the publicity, Mrs. D’Aquino was arrested and questioned by American military occupation authorities and the F.B.I. The United Press quoted her at the time as saying, “I didn’t think I was doing anything disloyal to America.”

In the fall of 1946, Mrs. D’Aquino was released from custody in Japan after the Army and the Justice Department concluded that there were no grounds for prosecuting her. But the Justice Department reopened the case in 1948. Loyalty issues were becoming a national political flashpoint, although mainly in the context of the Cold War, and the American Legion and the powerful columnist and broadcaster Walter Winchell had spoken out against Mrs. D’Aquino.

Mrs. D’Aquino, who had unsuccessfully sought permission from American authorities to return to California, was arrested on charges of treason, transported to San Francisco, held in a county jail for a year, then put on trial in 1949.

http://www.nytimes.com/2006/09/27/world/asia/28rose.html

No comments:

Post a Comment